Feature Article

The Hacker: A New Perspective

November 15, 2005

By MIKE POWERS

Senior Staff Writer

MOUNTAIN VIEW, California (The Times) - Kevin Smith sat in front of his computer monitor, typing wildly, jumping from window to window to get the job done. After ten minutes, he was finished. He undocked a USB thumbdrive and gave it to me.

“Just plug it into your Powerbook. See what happens.”

I obliged, and as soon as the computer realized the drive was there, an application window popped up. In seconds, it started copying a slew files to my hard drive. I started panicking--what if it was a virus? I didn’t trust him yet. He could be compromising my machine! When it finally finished, I received one final prompt from Kevin: “Now hit F8.”

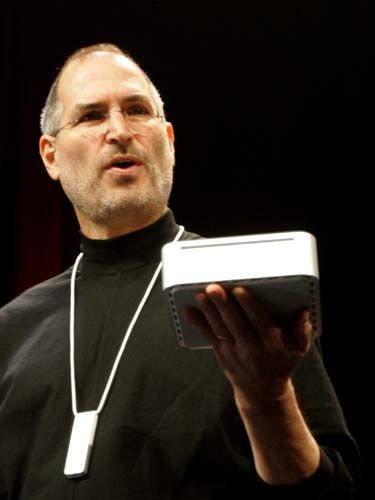

I heard a beautiful, glassy sound as the desktop receded from me and faded to black. I saw four icons parade around in elegant circles as they emerged from the bottom of the screen: Music, Photos, Video, DVD.

“This is Front Row!”, I said in astonishment. “You can’t buy this! You’re only supposed to get this with new iMacs!”

His response was resonant. “Why limit this beautiful app to the new iMac? Why not let it run on every single computer you own? People have a right to do what they want with their stuff.”

MisconceptionsAs a journalist, I can be quick to make judgments on how to approach a particular issue. After all, I deal with fast-breaking news on a daily basis. However, I must also try to rid my reports of personal bias.

I talked to Kevin based on his response to my previous article, “Hackers Responsible For $2 Billion Loss In DVD Sales”. He sent me a well-mannered e-mail stating that, contrary to my report, he was not to blame for lagging Hollywood revenues:

Dear Sir:

My name is Kevin Smith. You mentioned in your article that my workaround for encrypted DVDs, DeCSS, was responsible for billions of dollars of lost revenue in the motion picture industry. I will admit that many people have been using my software to illegally share DVDs with peers. However, this was not my intent: I created the software so that people could enjoy the peace of mind of having a backup copy of their movies. I do not wish to be associated with criminal acts simply because I made a product that can be used maliciously. Ford makes cars with the intent that most people will use them to go to work or school--not use them as murder weapons.

Sincerely,

Kevin Smith

Prior to reading this letter, I thought of a hacker as a criminal pulling confidential information off the internet for his own financial gain. This is a very common archetype in film and television: the rouge nerd helps the rest of his cronies by taking over the victim’s computer system. I see similar real-world stories come through the Times quite often.

However, I discovered that these accounts aren’t terribly representative. According to Kevin, these “black hackers” do exist, but there are very few of them: “I don’t like the negative connotation people give to the word ‘hacker’. Most of the hackers you see in the paper commit their crimes in countries where the economy is so poor they can’t find a legitimate source of income.”

He’s right: individuals impoverished by poor post-Soviet economies are notorious for developing some of the worst spyware, worms, and viruses. Instead of picking pockets, they turn to an affluent American’s Paypal account or a hole in an online banking system. They have nothing better to do than learn how to steal people’s information.

I was shocked when I asked Kevin to describe the most common kind of hacker:

“These are people who work on free applications, report bugs to commercial software publishers, tweak existing programs and, like me, work around annoying digital rights management systems.”

Unlike the archetype seen in media, a hacker’s work is not done for individual gain, but rather for the greater good of the computing community.

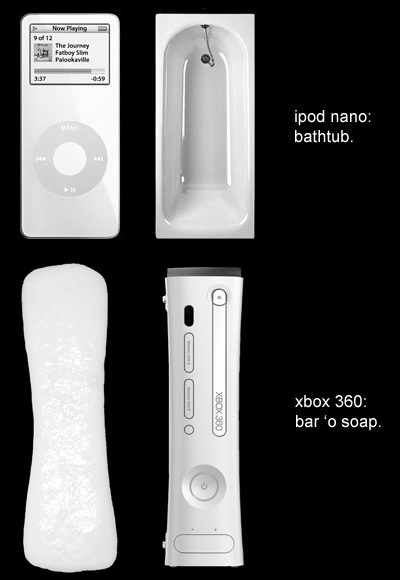

The Hacker’s NatureIt is clear that from Kevin’s response to the lock-down of Front Row that hackers hate restrictions. They want to be able to take apart or modify a piece of software just like they can take apart or modify their cars. Before computing became mainstream, this was a relatively easy task; most digital data was simple and open for introspection. However, as time went on, software became constrained in nature. Business administrators were worried that they day they released their product would be they day it fell out of their control.

This overprotective disposition is responsible for one of the main restrictions facing hackers today: the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. This law, passed in 1999, makes it illegal to tamper with digital data in a way that breaks content-protection mechanisms.

Now, hackers find themselves in a predicament. It is their nature to tinker with the things they purchase. If hackers like Kevin can’t modify protected digital code, they are denied thousands of opportunities to innovate and share useful modifications with one another. It has led him to calling lobbyists for data-protection schemes “the hacker’s greatest oppressor”.

Hackers have not lost the ability to fiddle with all protected code. If a modification is not done for commercial gain, and kept to a relatively private community, then it is dismissed as a harmless abnormality by the content owner. However, if code is changed and the alteration distributed to a wide audience, the hacker is open to litigation.

Kevin likens this to “someone suing you for putting third-party parts in your car. It’s ridiculous. It keeps you from doing what you want to do with something you have already paid for.”

A New PerspectiveI have reevaluated myself in writing this followup article. I was once biased towards the traditional view of the hacker community as being thieves and self-centered loners. Kevin was an unfortunate victim of this misunderstanding in my first article.

This bias could have come from any number of influences, but I am almost certain that some of it came from my own profession. It is my job to create content. This newspaper is owned by AOL Time-Warner, a major media conglomerate that manages both print and electronic properties. The atmosphere this newspaper creates in is inherently opposed to third-party modification.

However, Kevin makes a good point: “you already paid for this newspaper. You can cross out phrases, tear out snippets, do the jumble, or make it into a boat to float down a river. It’s your paper now. You should be able to do what you want with it.”